Before the advent of the NHS in 1948, hospitals in Britain were largely dependent on voluntary contributions and donations from wealthy elites, community fundraising, and charitable income. Healthcare was largely privatised and access to treatment was determined by one's ability to pay. The Poor Law system provided basic healthcare in workhouses, but the conditions were often poor and families were usually separated. Voluntary hospitals, funded by donations and run by volunteers, provided another avenue for the poor to access healthcare. These hospitals often focused on treating specific conditions or groups of people. The emergence of National Insurance in 1911 provided some protection for workers against the risk of illness, but it excluded wives and children of members and did not cover hospital treatment. Friendly societies and various community-owned mutual aid funds and medical clubs provided alternative avenues for working-class families to access healthcare, but these schemes had limitations and were not always reliable.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Healthcare access | Dependent on the ability to pay for treatment |

| Available for free or at a low cost through a patchwork of different services with varying levels of quality and access | |

| Voluntary hospitals provided access to healthcare for the poor | |

| National Insurance provided workers with protection against the risk of falling ill and being unable to work | |

| Working-class families accessed healthcare through friendly societies | |

| Community-owned mutual aid funds and medical clubs provided access to healthcare for working people | |

| Middle-class individuals had access to health insurance schemes | |

| The Poor Law set out the responsibilities of local areas to provide help for those in need | |

| The middle class was largely excluded from hospital treatment and had to rely on expensive private doctors | |

| Healthcare was mainly provided by charities, poor law, and an unregulated private sector | |

| National Insurance Act of 1911 provided access to general practitioners for manual labourers and lower-paid non-manual workers | |

| Wives and children of National Insurance members were excluded from coverage | |

| Hospitals were founded and funded by the middle and upper classes | |

| Patients were generally required to pay for their healthcare |

What You'll Learn

Hospitals were funded by donations and run by volunteers

Before the advent of the NHS, hospitals were funded by donations and run by volunteers. The quality of healthcare was largely dependent on one's ability to pay for treatment. The Poor Law set out the responsibilities of local areas to provide aid for those in need, including the elderly, single mothers, and people with disabilities. This aid was often provided through workhouses, which offered basic food, clothing, and healthcare in exchange for manual labour. Many people feared going to these workhouses due to their poor conditions, and families were usually separated.

Voluntary hospitals, funded by donations and staffed by volunteers, provided access to healthcare for those who couldn't afford private treatment. These hospitals often focused on treating specific conditions or groups of people. For example, The Foundling Hospital in London cared for children abandoned by their parents, while the Bradford Royal Ear and Eye Hospital in West Yorkshire specialised in treating ear and eye conditions. In the early 20th century, a third of hospital beds in England were provided by these voluntary hospitals.

Working-class families accessed healthcare through friendly societies, which provided sickness, funeral, and other benefits to members in exchange for weekly subscriptions. These societies also arranged contracts with general practitioners (GPs) to provide healthcare to their members. Additionally, various community-owned mutual aid funds and medical clubs allowed working people to pay in advance for access to doctors, medicines, and sometimes hospital treatment.

Before 1900, healthcare was primarily provided by charities, the Poor Law, and an unregulated private sector. However, between 1900 and 1948, a shift occurred, with the development of a highly effective mixed economy of mutual payment schemes, local authority services, and not-for-profit providers. The introduction of National Insurance in 1911 further changed the landscape, providing access to GPs and tuberculosis care for manual labourers and lower-paid workers.

The Science of Sleep: Hospital Edition

You may want to see also

Healthcare was dependent on ability to pay

Before the introduction of the NHS in 1948, healthcare in Britain was largely dependent on one's ability to pay for treatment. While some level of free or cheap healthcare was available, it was provided by a patchwork of different services that varied in quality and accessibility.

The Poor Law, which was in force during the 19th century, outlined the responsibilities of local areas to provide aid for those in need, including the elderly, single mothers in childbirth, and people with physical, mental, or learning disabilities. This aid typically took the form of workhouses, which provided basic food, clothing, and healthcare in exchange for manual labour. However, workhouses were often associated with poverty and poor conditions, and families were usually separated, making them a feared option for many.

For those who couldn't afford private healthcare, voluntary hospitals provided another option. These hospitals were funded by donations and staffed by volunteers. By the early 20th century, a third of hospital beds in England were provided by these voluntary hospitals, which often focused on treating specific conditions or groups of people.

Working-class families also had access to healthcare through friendly societies and 'works schemes'. Friendly societies provided sickness, funeral, and other benefits to eligible members in exchange for weekly subscriptions, and they often arranged contracts with GPs to provide healthcare to their members. 'Works schemes' involved workers in certain industries agreeing to deductions from their wages to fund a 'works surgeon' or 'works doctor' to provide healthcare. However, these schemes often excluded the wives and children of members, leaving them vulnerable and reliant on other options such as older workers' insurance schemes, free clinics, and advice from visiting pharmacists.

The National Insurance Act of 1911 provided access to general practitioners (GPs) for manual labourers and lower-paid non-manual workers earning below a certain income, as well as tuberculosis care. Over time, changes to income limits expanded coverage, and by 1936, half the adult population was included. However, fees for GPs were increasing for those outside the system, such as the middle class and the wealthy.

In summary, healthcare before the NHS was fragmented and unequal, with access and quality of care largely determined by one's ability to pay. The introduction of the NHS in 1948 marked a significant shift towards providing universal healthcare that was free at the point of delivery, removing the financial barriers that had previously existed.

Where is Van Buren Animal Hospital Located?

You may want to see also

Friendly societies provided healthcare to eligible members

Friendly societies were a way for like-minded people to form social networks and pool their resources to support each other in times of need. Their success also made them a significant healthcare provider in Britain before the creation of the National Health Service. Friendly societies offered a subscription-based model for their members. These funds provided members with access to a doctor for advice and offered them a safety net.

The Friendly Societies Act 1829 and other legislation around their financial and social regulation influenced subsequent legislation for provident societies, co-operative societies, building societies, and trade unions. Well-run, democratic 'friendlies' such as Tredegar provided useful but not exclusive models for the NHS. However, there were also examples of badly run societies. Some went bankrupt, others were corrupt, and some of the doctors they engaged were incompetent or unethical.

Friendly societies provided sickness, funeral, and other benefits to eligible members in return for weekly subscriptions. Many such societies also arranged contracts with GPs to provide healthcare to their members from the late 19th century onwards. Apart from friendly societies, a range of different 'works schemes' emerged in the 19th century whereby workers in any mine, foundry, mill, or factory agreed to the deduction of a sum of money from their wages and to the appointment of a 'works surgeon' or 'works doctor' to provide healthcare.

In the early 20th century, a third of hospital beds in England were provided by voluntary hospitals. Voluntary hospitals often focused on treating specific conditions or groups of people. For example, the Foundling Hospital in London cared for children who were abandoned by their parents. In West Yorkshire, ear and eye conditions were treated at Bradford Royal Ear and Eye Hospital.

Before the NHS, Britain had a mixed economy of healthcare, blending private, public, and voluntary provision. By 1900, there were around 800 voluntary hospitals providing acute care, funded largely by philanthropy. The local state provided institutional care through the Poor Law, though mostly in low-quality, stigmatizing workhouses. Local government also delivered public health services, both environmental and increasingly clinical, for mothers, children, and infectious disease sufferers. Primary care was partly commercial and partly accessed through friendly societies, a form of sickness insurance rooted in working-class culture.

Barbados Hospitals: World-Class Care and Service

You may want to see also

Work schemes provided healthcare to workers

Before the introduction of the NHS in 1948, access to healthcare in Britain was largely dependent on one's ability to pay for treatment. While healthcare was available for free or at a low cost, the quality and accessibility of these services varied.

The Poor Law, which was enacted in the 19th century, outlined the responsibilities of local areas to provide aid for those in need, including the elderly and the sick. This aid was typically provided through workhouses, which offered basic food, clothing, and healthcare in exchange for manual labour. However, workhouses were notorious for their poor conditions, and families were often separated.

For those who weren't living in workhouses, voluntary hospitals provided access to healthcare. These hospitals relied on donations and volunteer staff and often focused on treating specific conditions or groups of people.

In 1911, the National Insurance Act was introduced, providing workers with some protection against the financial risks of illness. This scheme allowed workers who contributed to see approved doctors and receive treatment for certain conditions, such as tuberculosis. However, it did not cover family members. By 1946, 21 million people in Britain, or 40% of the population, had access to a GP through National Insurance.

There were also community-owned mutual aid funds and medical clubs that working people could pay into and receive access to doctors, medicines, and sometimes hospital treatment.

Despite these schemes, many people struggled to afford treatment, particularly those in the lower middle class. This struggle led to a growing appetite for social welfare services after World War II, which ultimately contributed to the development of the NHS and its principle of providing healthcare free at the point of delivery.

Measuring Weight: Hospital Methods Explained

You may want to see also

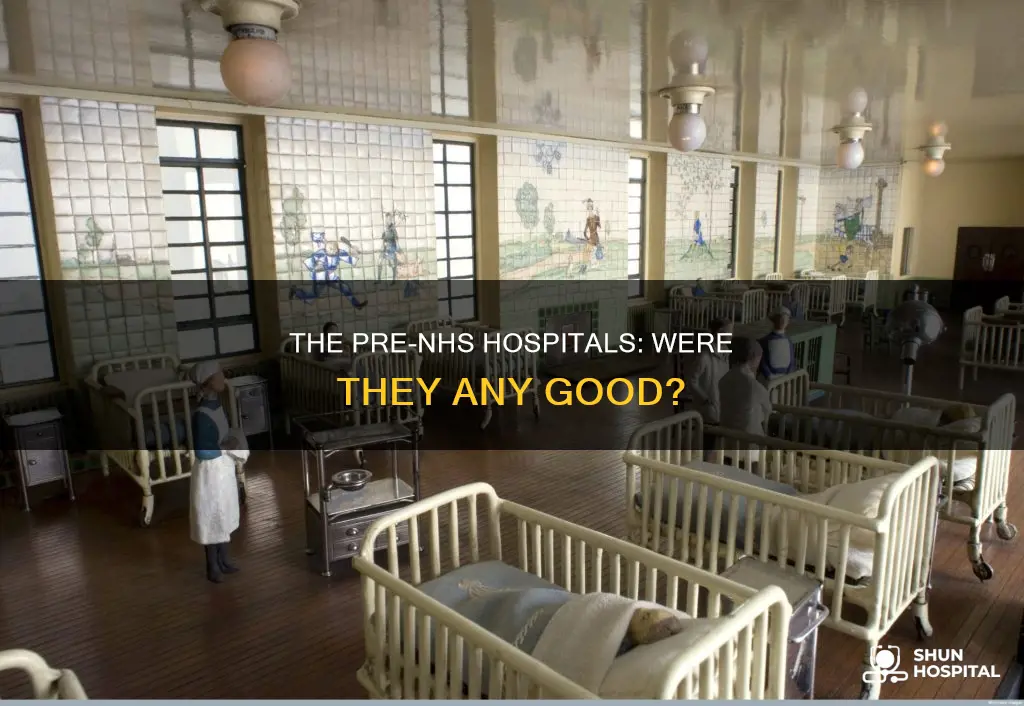

Hospitals were founded and funded by the middle and upper classes

Hospitals before the NHS were largely founded and funded by the middle and upper classes. The British healthcare system before the NHS was possibly the best in the world, with a highly effective mix of mutual payment schemes, local authority services, and not-for-profit providers. However, access to healthcare was largely dependent on one's ability to pay for treatment.

The Poor Law set out the responsibilities of local areas to provide aid for those in need, including older people and the ill. This aid was often provided through workhouses, which supplied basic food, clothing, and healthcare in exchange for manual labour. Many people feared going to these workhouses due to their poor conditions, and families were usually separated.

For those who could not afford private healthcare, voluntary hospitals provided access to healthcare. These hospitals were funded by donations and run by volunteers. By the early 20th century, a third of hospital beds in England were provided by these voluntary hospitals. They often focused on treating specific conditions or groups of people. For example, The Foundling Hospital in London cared for children who had been abandoned by their parents.

There were also health insurance schemes available to middle-class individuals, which helped them meet the substantial costs of treatment in private rooms, nursing homes, or their own homes. Working-class people could access healthcare through friendly societies, which provided sickness, funeral, and other benefits to eligible members in return for weekly subscriptions.

Community-owned mutual aid funds and medical clubs were another way for working people to access healthcare. Members paid into these funds when they could afford to and, in return, received access to doctors, medicines, and sometimes hospital treatment.

Overall, while hospitals before the NHS were founded and funded by the middle and upper classes, there were a variety of institutions serving the needs of different social classes. However, access to healthcare was often challenging for those who could not afford to pay, and the quality and availability of care varied depending on one's location and financial situation.

Raising Funds for a Child's Hospital Stay

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Hospitals before the NHS were associated with poverty, and those who could afford it would opt for private healthcare instead. Hospitals were funded by voluntary contributions and donations from wealthy elites, community fundraising, and other charitable income sources. They ranged from large, prestigious hospitals in London to small cottage hospitals across the country.

Before the NHS, access to healthcare was largely dependent on one's ability to pay for treatment. Various schemes existed, including community-owned mutual aid funds and medical clubs, where members paid in advance for access to doctors, medicines, and sometimes hospital treatment.

The schemes typically covered working people and, in some cases, their families. The National Insurance Act of 1911 provided access to general practitioners (GPs) for manual labourers and lower-paid non-manual workers earning below a certain income. However, wives and children of members were often excluded from these schemes.

Lady almoners were women who decided how much patients should pay for treatment and helped ensure they received support after leaving the hospital.

Healthcare before the NHS was often unaffordable for many, especially the poor and the emerging lower middle class. The quality and access to healthcare varied, and there was a mix of private, municipal, and charity schemes. The middle class was largely excluded from hospital treatment and had to rely on expensive private doctors and sub-standard nursing homes.